Last week, an Amazon book review shocked me, not so much because somebody wrote a negative review of one of my books but because it appeared at first to have been written about a different book, not mine. After reading over, several times, the comments by “WS,” I came to better understand why his book review appeared unrelated to Live Pterosaurs in Australia and in Papua New Guinea. WS had become upset because his comfortable assumptions about one or more popular standard-model axioms of science had been challenged in his reading of my book.

Definition of “Science”

It appears that WS’s personal definition of “science” includes something like this: All dinosaurs and pterosaurs became extinct millions of years ago. He wrote nothing like that in his book review, so how did I come to that conclusion? Notice what he did write:

“A large portion of it is devoted to the author’s antiscience rhetoric . . .”

“Rhetoric” is a word sometimes chosen by someone offended by another’s words, and it is used to belittle ideas with which one disagrees, therefore we can dispense with that word after acknowledging that WS disagrees with something I have written.

I have found some clues that suggest WS has been careless in his reading and thinking. If he had looked more closely at the Amazon Book Description, he would have noticed this: “Learn for yourself what many scientists never imagine.” The book contradicts a common assumption held by many scientists. (I’m sure many purchasers of many Amazon books fail to read all the contents of the Book Descriptions; WS may be typical.)

Of course I could have been more careful myself, in writing that Amazon Book Description, making it easier for potential readers to know that the subject is controversial and contrary to deeply held assumptions about extinction. But WS seems to have also been careless while reading the book.

Perhaps the following paragraph in the book can help explain why WS chose the word “antiscience:”

Some eyewitnesses fear discovering the monstrous possibility of personal insanity. Others fear not insanity itself but the opinions of anyone who might think them insane. Others fear discovering that some of what they had been taught about science was false; they prefer to believe that scientific proclamations must always be true. How grateful I am for those who, in spite of their fears, report to me their encounters!

I believe that WS read the sentence that included “scientific proclamations” and realized I was fighting against one or more of those proclamations, so that reader concluded that I was against science, in other words my writings are “antiscience.” But how great is the difference between scientific proclamations and science!

Any scientist can proclaim a new idea, be it classified as a conjecture, hypothesis, or theory. What if that idea contradicts a popular idea held by many scientists? Such a submission of an idea does not mean that the scientist has become transformed into an anti-scientist. In fact, holding too firmly to a scientific axiom might actually be a problem, especially if significant evidence appears to contradict the axiom.

I believe that WS was unprepared for the book Live Pterosaurs in Australia and in Papua New Guinea. He was unwilling to consider the possibility that a popular axiom of biology might be faulty or just plain wrong.

Four Chapters – Four Sightings

This reviewer of my book Live Pterosaurs in Australia and in Papua New Guinea wrote this:

“The book really consists of one or two intriguing reports . . .”

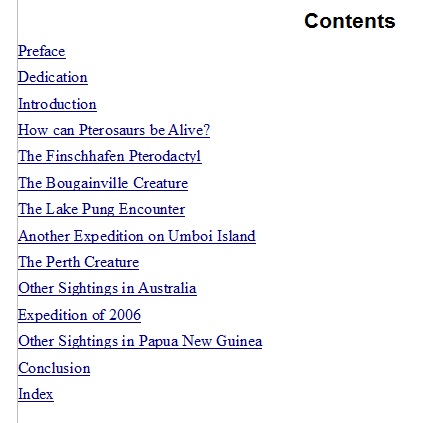

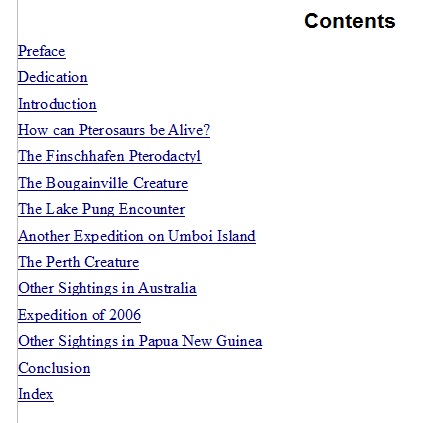

Let’s move away from WS’s personal opinion about what is or is not “intriguing,” for his statement about numbers of reports can seriously mislead people who read his book review. Four of the chapters shown in the above image of the Table of Contents are each devoted to a sighting report; those are the key sightings, critical to understanding the credibility of pterosaur sightings in general. The book also contains other sightings, a good number, notwithstanding WS’s statement about “one or two.”

The four key sightings (each with a chapter of its own) are these:

- The Finschhafen Pterodactyl

- The Bougainville Creature

- The Lake Pung Encounter

- The Perth Creature

Here’s a part of what’s found in the chapter “The Bougainville Creature:”

The creature I saw one early morning in Bougainville is etched in my memory. . . . I actually heard it before I saw it. A slow flap…flap…flapping sound. The air was still, and our truck had stopped on our downward journey from the top of the range to the coast way below. The sound was amplified by the road-cutting into the mountain. That is, there was bare red/orange clay, rather than the surrounding jungle.

I can’t remember why our vehicle had stopped. Maybe we had to wait for another vehicle to pass us. I don’t know. But I can still hear that slow flapping sound in the stillness of an early tropical morn, on the road from Panguna down to Loloho on Bougainville Island in 1971.

When I looked up . . . I saw a very unusual creature. Firstly, it was very big (wingspan at least 2 metres, probably more . . . possibly much, much more). I can’t remember the exact distance estimate that this creature was from me . . . It was black or dark brown. I had never seen anything like it before. It certainly looked prehistoric, in that it did not look like any other bird that I have seen before or since.

Why prehistoric? Well, maybe my memory has been influenced by the intervening years, but I recall seeing this creature with a longish narrow tail . . . the head was disproportionately large compared to the body (no feathers in sight). The wingspan was large. The head had no ‘normal’ beak. Rather there seemed to be . . . a kind of beak that was indistinguishable from the head, and the head seemed to continue this ‘point’ at the back of the head. There was a clear line running from the ‘beak’ to the back of the head..where the ‘line’ continued to protrude . . .

For those who were previously unaware of the eyewitness in this sighting, don’t assume Brian Hennessy is crazy for seeing such a thing. Mr. Hennessy is himself a professional psychologist.

###

Commenting on a Review of a Pterosaur Book

Consider WS’s declaration: “The book really consists of one or two intriguing reports . . .” Without the word “intriguing,” that statement is patently false. With the word, WS is declaring his opinion or his personal interest in a small portion of the sighting reports. But WS’s statement can be misleading, for no mention is made about the many sighting reports investigated in the book, the many reports that he personally does not find intriguing.

.

Non-fiction cryptozoology: Live Pterosaurs in Australia and in Papua New Guinea

Part of the Preface:

You will here find reports of encounters with apparent living pterosaurs, including many accounts never before published in any book. Other sighting reports are condensed from the print book “Searching for Ropens.” The ebook you are now examining is neither exhaustive nor rudimentary, but it explains most of what most Australians, and others, need to know about what might, on rare occasions, fly over their heads at night.

.